Cognitive Interviewing - A Brief Guide

The cognitive interview was originally developed by Fisher, Geiselman, and their associates (1984). They list four key elements that aid memory retrieval: context reinstatement, reporting everything, recalling the incident from different perspectives, and changing the temporal order of recall. The cognitive interview has been modified in several ways over the years to address problems with it, and the application of it. The primary changes have included the need for the inclusion of interpersonal/communication-based psychology, in its application.

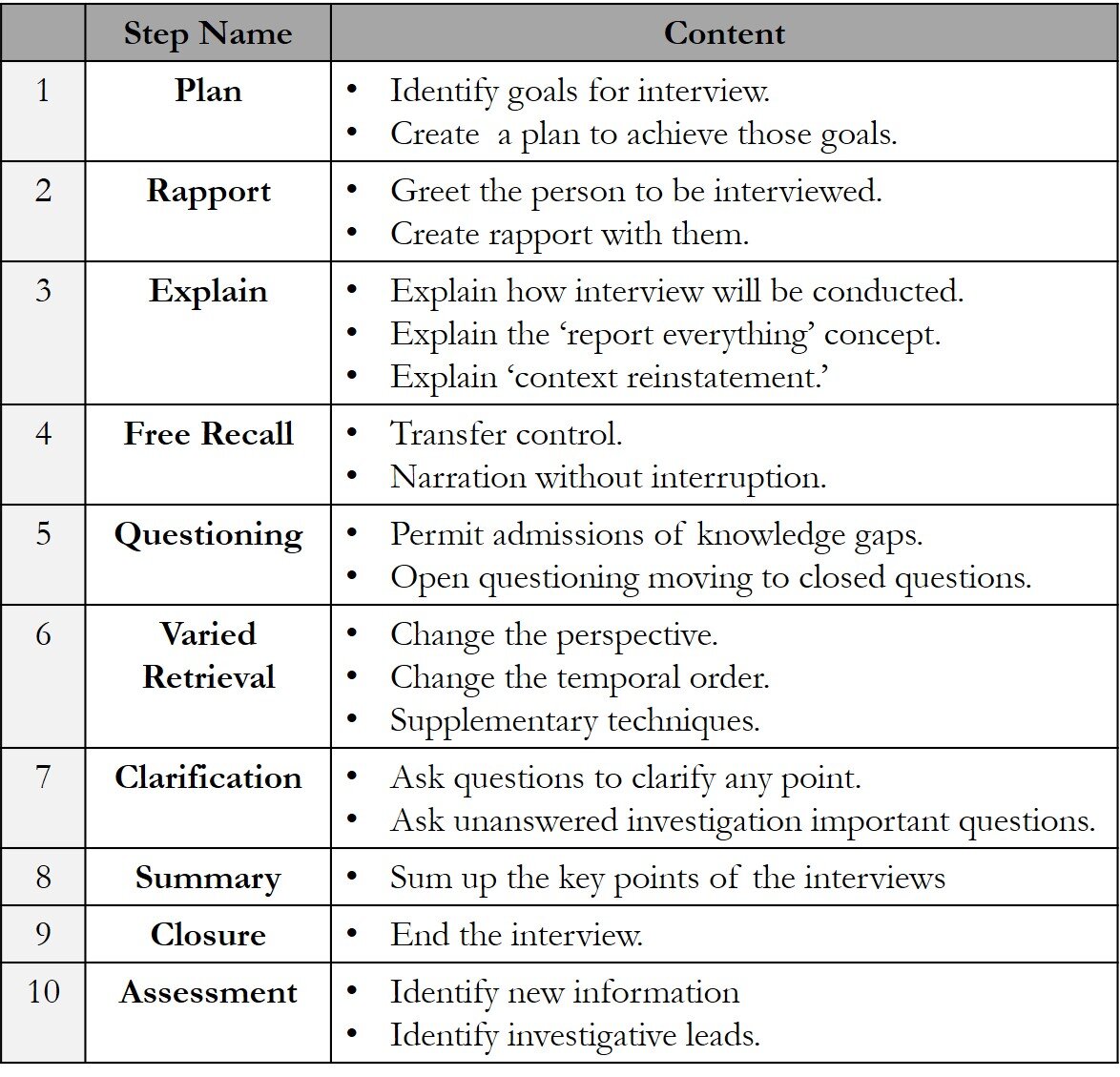

Research has established the effectiveness of the cognitive interview in the interviews of witnesses, victims, and suspects. Cognitive interviewing reliably enhances the process of memory retrieval and elicits more information without generating inaccurate accounts. It works. It is the best method for obtaining the most accurate information. Its main downsides are the time it takes to carry out and the fact that officers are not trained properly in it. We include brief details of the methodology because it is important. However, this is no substitute for proper training in the methodology. The diagram illustrates each step that is taken in a cognitive interview. In the diagram the steps are followed by a summary of what should take place in each step.

Step 1 in the process is to have a plan. Interviews are about fact finding. Officers should identify what they want to achieve and design a plan to get there. Options include adopting a non-structured approach with a limited number of identified questions or a highly structured approach where both questions and their sequencing are prepared before commencing. The approach will be dictated by the seriousness of the crime, and the amount of time available. Having no plan is likely to result in things being missed.

Step 2 is where the officer greets the person to be interviewed and attempts to build a degree of rapport with them. Regardless of whether or not the person is witness, victim or suspect, it is good to commence an interview in a civil way. This step will include any formal introductions required under law.

Step 3 is where the officer explains to the person what will happen during the interview. While technical language is used here to explain ideas, the officer will have to find appropriate ways of explaining the concepts to the person. Giving the person an easily understood explanation of what is happening, makes it more likely that they will engage with the process. The person should be given an opportunity to ask questions or to clarify what they have to do. The officer should explain what we mean by the technique of reporting everything. This is a critical part of cognitive interviewing. Often a person may only wish to give details of which they are absolutely certain. They will not give incomplete details. The officer should explain to the person that some people hold back on information because they don’t know what is important or what may be useful. The person should be encouraged to provide even trivial details that lie within their knowledge. The officer should tell the source to assume that they, the officer, does not know anything. ‘I wasn’t there. I don’t know what happened. You were. Tell me everything.’ At the outset it can be beneficial for the officer to provide an example of what they mean by the term report everything.

The next thing that needs explained is context reinstatement. Cognitive interviewing theory asserts that the closer the context is in which the memory is recalled, to when the memory was encoded, then the greater the quality of the recall is likely to be. People are usually able to remember more information if they are in the same place as when they learned it or first created the memory. The concept here is that what the person was experiencing at the time of the event is likely to provide links to when the memory was stored. If the storage context can be recreated, then the links to the memories can be created and the memories accessed. The officer should ask the person to mentally reinstate the context of the event. We want them to picture the place where the event occurred, as clearly as possible in their mind. If they are encouraged to envision everything that was happening at the time of the event, the more of the event they are likely to remember. The officer say to the person something akin to: ‘I want you to think back to before you entered the bar. Put yourself back there. Think about everything that was going on. Everything you were hearing and seeing. Think about how you were feeling and what you were wearing. If it makes it easier close your eyes. In your mind recreate the circumstances.’

Step 4 is about encouraging the free recall of the event. Free recall occurs when the person is encouraged to recount information without interruption. Officers should not interrupt the person for any reason. Some officers find this all but impossible. They have an almost obsessive need to control every aspect of an interaction. Officers in this phase must use active listening techniques including non-verbal encouragement. Before commencing the free recall the officer transfers control of what happens over to the person. ‘It is over to you. Just tell me what happened. During free recall the source should be encouraged to start from where they want. At this step chronology is unimportant. No effort should be made to try to get the person to tell things in order.

Step 5 is about questioning the person to obtain greater detail about what has happened. This should be done in a non-confrontational way, continuing to encourage the person to report everything. Questions should be used in a limited way. They are not meant to be a blunt instrument. If poor questions are asked, they will distort the way a memory is recalled. The person should be reassured that if there exist gaps in their knowledge. Questions should begin open and move to more closed to clarify specific points of interest.

Step 6 is entitled varied retrieval There are two elements in this step. Varied retrieval involves using three techniques to access a memory differently. If time permits all three can be used or the officer may choose which technique to use depending on what they are seeking to achieve. The first varied retrieval technique is referred to as change perspective. Change perspective involves getting the person to retell the information from a different perspective. This changed perspective can cue the recall of additional details. It causes the person to access different aspects of memory and uses different cues. For example, the person is asked to imagine seeing the event from another’s perspective. ‘Tell me what the waiter would have seen.’ Alternatively, they are asked to imagine what they would have seen had they been viewing it from a different place. ‘Imagine you had been across the room, what would you have seen?’

The second technique is referred to as change temporal order. We all tend to work from the beginning of an event through to the end. By asking the person to tell the story from the end and backward, they may recall different details. Alternatively, we can ask them to start from the point that is most salient for them. This is actually where many people will start a story normally.

The third technique is the use of retrieval prompts. Retrieval prompts involve using cues to stimulate how the person accesses memory Asking a person to act out what happened may aid recall. ‘Act out what happened from when you came into the room.’ The person gets up and goes to the door and acts out the event from there. ‘I came in. Joe was on my right and Pedro was on the left. Mike was up at the bar…’ Another useful retrieval prompt is to get the person to draw out the location. The person is told to include anything they want and describe everything as they are drawing it. They then talk through what happened using the sketch as an aid. As they do so they generate their retrieval cues. Asking the person to think in terms of the 5 senses i.e. hearing, seeing, smell, taste, and touch will help in their recollection of the event.

Step 7 involves the clarification of any ambiguities that have arisen. It is also the time to ask any questions that are important for the investigation, that the witness has not answered to that point. This may be simply because they do not know the answer, of because they did not realize its significance.

Step 8 is about providing a summary of the salient points of the interview. This allows the person to confirm or amend any point.

Step 9 is about the closure of the interview. The person should be given and outline of what happens next and provided with the opportunity to ask any questions.

Step 10 is the assessment of how the interview went. Primarily, this will be about assessing how the interview has helped or hindered the investigation and deciding what steps to take next. It is also a good opportunity for the officer to self-assess their performance or to ask a colleague that was present for feedback. This is particularly important for an officer who is learning to interview.

Cognitive interviews can be used for victims, witnesses and for suspects. With suspects the officer will want to take more time in planning the interview. They will also need to be sure of regulations as to when and to what extent a lawyer may interrupt. Frequent interruptions will be detrimental for everyone in the truth-seeking process. Interviewing is about seeking truth, not a confession. The cognitive interview is the most academically sound method of obtaining the maximum amount of accurate information. Officers need to know all elements of it, and not just those that fit in a nice mnemonic. (Like PEACE).

This is an extract taken from our forthcoming book “Interpersonal Skills for Police Officers” expected February 2020.

For more information on our interview training email info@hsmtraining.com

References

Geiselman, R. E., Fisher, R. P., Firstenberg, I. Hutton, L. A., Sullivan, S. J., Avetissain, I. V., Prosk, A. L. (1984). Enhancement of eyewitness memory: An empirical evaluation of the cognitive interview. Journal of Police Science and Administration, 12[1], 74-80.